Hillsborough Florida Pioneer and Settler Seth Howard at the Beginning of the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War is considered to have officially begun on December 23, 1835, when 110 enlisted men marched out of Fort Brooke (Tampa, Hillsborough County) under the command of Bvt-Major Francis L Dade to relieve the Company of men stationed at Fort King (close to modern-day Ocala, Marion County).

Tensions with the Seminoles in the area were high. My 4th great-grandfather, Seth Howard, had settled in an area of Hillsborough known as Simmons Hammock. He would later officially acquire this land through the Armed Occupation Act of 1842.

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSPL-TSNC-R?i=1440&cat=540006; United States, Florida; Armed occupation act settlers records, 1842-1843; Land permits, Knight, John, no. 171-Z The following are not found in index: Abandoned or annulled permits Notices, refusals, acceptances, land claims, permits and surveys; Film # 008570270; Images 1441-1443 of 1768; Land Application 299

I had completed many literature searches on the name of “Seth Howard” and I felt that I had found everything relevant that I could. I decided to do a literature search for “Simmons Hammock” to see if there was any information about the area that was documented. I came across an article about the modern-day community of Seffner as part of the Hillsborough Historic Resources Survey Report.

https://hillsborough.wateratlas.usf.edu/upload/documents/HILLSBOROUGH_COUNTY_Historic_Resources_Excerpts_Seffner.pdf

And there was the mention of the “Howard” surname, living in Simmons Hammock, at just the right period. But I didn’t want to accept published literature without checking the sources. The paragraph above was sourced as such:

Bruton and Bailey, Plant City, 22

Plant City, Its Origin and History by Quintilla Greer Bruton and David E Bailey published in 1984. On page 22 it states, “The Hammock was named for Reverend Daniel Simmons, an intrepid Baptist missionary, who settled in the rich hammock in 1829. Reverend Simmons came from Savannah, Georgia, to establish a mission in Indian territory and may have been the first white man to settle in what is now the Plant City area. He won the respect and friendship of the Seminoles and in 1835, when they prepared, to go on the war-path, they warned him of impending danger advised him to leave. Loading his possessions in an ox-cart he and his wife, with their daughter Elizabeth, went to Fort Brooke where they remained for a few months, then left the state, going to Mobile, Alabama."

There is no mention of Seth Howard in this source.

Covington, The Story of Southwestern Florida, Volume I, 82

The Story of Southwest Florida Vol I by James Warren Covington, published in 1957. On page 82 it states, “The Hammock was named for Reverend Daniel Simmons, an intrepid Baptist missionary, who settled in the rich hammock in 1829. Reverend Simmons came from Savannah, Georgia, to establish a mission in Indian territory and may have been the first white man to settle in what is now the Plant City area. He won the respect and friendship of the Seminoles and in 1835, when they prepared, to go on the war-path, they warned him of impending danger advised him to leave. Loading his possessions in an ox-cart he and his wife, with their daughter Elizabeth, went to Fort Brooke where they remained for a few months, then left the state, going to Mobile, Alabama."

Again, there is no mention of Seth Howard in this source.

Major General George A. McCall, Letters From The Frontiers. Facsimile Reproduction. (Gainesville, FL: University Presses of Florida, 1974[1868]), 299-307

Letters From the Frontiers. Published letters of Major General George A. McCall (https://ufdc.ufl.edu/uf00100326/00001). On pages 299-307, it states:

There is still no mention of Seth Howard in this source.

At this point, I was having trouble locating Pioneer Florida, Vol II by D.B. McKay. Lots of libraries had copies, but none had been willing to send them to me to view through interlibrary loan because they were reference books. I felt that I had searched thoroughly online for the books as well. But I knew that D.B. McKay wrote a column in the newspaper entitled Pioneer Florida, so I had a hunch that this book was likely just all of his articles, reprinted in one single resource. So, I did a search for relevant articles in online newspaper sources, which led me to this article (which has many errors in its specific details):

Disappointingly, there was still no mention of Seth Howard. Where in the world had the article printed as part of the Hillsborough Historic Resources Survey Report gotten the information regarding the Howard and Saunders families also fleeing to Fort Brooke while their homesteads burned?

I wondered if this was just an assumption made by the writers and researchers based on the fact that Seth Howard also settled in the area and would not have been allowed to safely remain, and thus HAD to have fled?

I continued to do a literature review on Dade’s Massacre. I found a book at my local library entitled Dade’s Last Command by Frank Laumer printed in 1995. This book is wonderful, and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in learning more about the events leading up to as well as what transpired at Fort Brooke at the very beginning of the Second Seminole War. It is written in a narrative form but is based on primary source documents. I found it very easy to read and it is well-sourced. As I followed the sourcing listed in this book, it led me to the following letter written by General Belton to General Jones on December 12, 1835.

General Belton was in command of Fort Brooke once he arrived from Mobile, Alabama in December 1835.

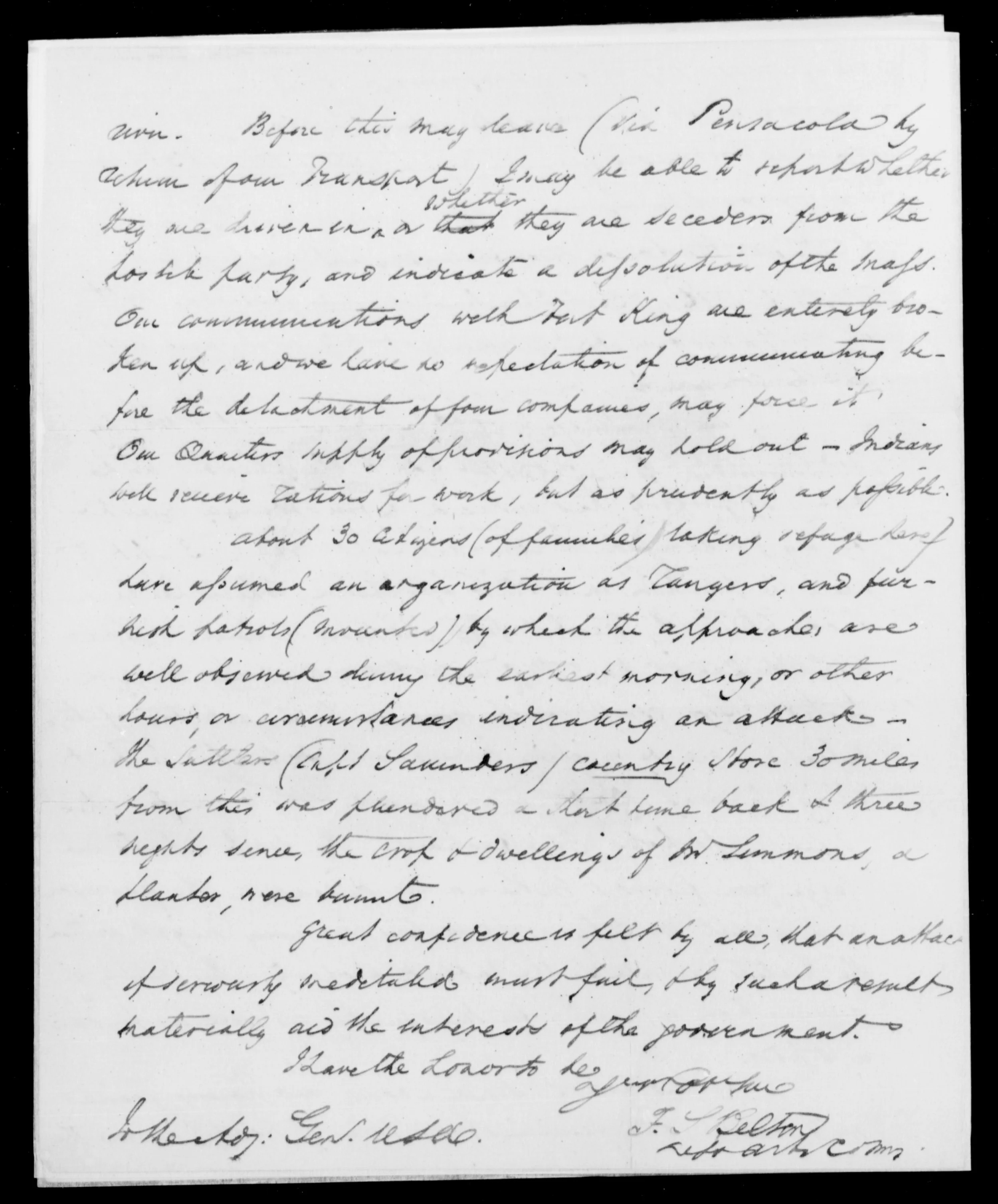

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/28434757

National Archives; Record Group 94: Records of the Adjutant General's Office; Series: Letters Received; Belton Letter, December 12, 1835, Orderly Book, Company B, Records of U.S. Regular Army Mobile Units; 4 pages

His handwriting is very difficult to read, but I’ve transcribed it as well as I can, and here is what I can make out (the bolded portions were emphasized by me to bring attention to facts as they relate to Seth Howard):

“Fort Brooke Florida

Sir, Dec 12, 1835

I have the honor to inform you that in obedience to

orders from Bvt. Brig. Genl. Clinch, I arrived yesterday with

my company from Fort Morgan, at this port, and assu-

med the command.

The excited state of the Indians in this vicinity

and the hostility demonstrated by the plunder and

burning of property has induced extraordinary exertions

by my predecessor in command, Capt Fraser 3[rd] Art[illary], to

place the position in a state of defense, which has been

accomplished by great energy and perseverance. Three

more companies from N Orleans & Key West are daily ex

pected. Two comp. of the garrison here, and two of those

expected, are by existing orders to be detached to Fort

King, leaving Dade, Zan(t)zingers & my own for this

defense, perhaps 90 effectives. The sick reports are

large from fevers & inflammatory diseases. The garrison

with about 100 citizens & families, are every night within

the pickets, as well as the publick property. The supply of

ammunition scanty, for musquetry as well as for our

2 6-p[oun]d[e]rs.

A few hours sense about 40 Indians joined

(with horses and families) our friendly party, across the

river). Before they may leave (via Pensacola by

schooner of our transport) I may be able to report whether

they are driven in or whether they are seceders from the

hostile party, and indicate a dissolution of the mass.

Our communications with Fort King are entirely bro-

ken up, and we have no expectation of communicating be-

fore the detachment of four companies, may force it

Our Quarters supply of provisions may hold out -- Indians

will receive rations for work, but as prudently as possible.

About 30 citizens (of families taking refuge here)

have assumed an organization as rangers, and fur-

nish patrols (invented) by which the approaches are

well observed during the earliest morning, or other

hours or circumstances indicating an attack -

the settlers (Capt Saunders County store 30 miles

from this was plundered a short time back & three

nights sence, the crops & dwellings of Mr. Simmons, a

planter, were burnt.

Great confidence is felt by all, that an attack

if sever[e]ly meditated must fail & by such a result

materially aid the interests of the government.

I have the honor to be

Your Obt Serv

To Bvt. Brig. Gen. USA F.S. Belton

Off. in Comm.”

This letter makes it clear that many more folks other than just Rev Simmons and his family were at Fort Brook for protection. This lends credence to the likelihood that Seth Howard is also at the fort, although he is not specifically mentioned. We finally have a mention of the Saunders family and the burning of Mr. Saunders’ store.

At this point, we might, as researchers, wonder if Seth Howard was definitely living in the area at this time. Per his Armed Occupation Act of 1842 application, the land description was given as “In the Hammock commonly known as Simmon's Hammock commencing at a stake planted in the Pine barren on the West side of the Hammock running from thence due east 160 rods to a stake on an Indian Mound, thence due south 160 rods to a blased bay tree from thence due west 160 rods to blased Pine tree in the Pine barren and from thence due north 160 rods to the place of beginning embracing one half mile square or one quarter section of land.”

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSPL-TSNC-R?i=1440&cat=540006; United States, Florida; Armed occupation act settlers records, 1842-1843; Land permits, Knight, John, no. 171-Z The following are not found in index: Abandoned or annulled permits Notices, refusals, acceptances, land claims, permits and surveys; Film # 008570270; Images 1441-1443 of 1768; Land Application 299

However, this application was submitted in 1842. When did Seth Howard arrive and settle in Simmons Hammock?

The earliest source material that I have been able to find of Seth Howard being in the area was the 1833 election held at the Tampa Bay Precinct of Alachua County in 1833. Note that Daniel Simmons and William G Saunders also appear as voters in this election at the Tampa Bay Precinct as well.

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSPL-19BP-2?i=167&cat=542643

United States, Florida; Voters Registers; Florida territorial and state election records, 1826-1865; Alachua - Columbia (precinct no.11, 2 Oct 1848); Images 168-170 of 1846

By 1835, Hillsborough County had been created from Alachua County and Seth Howard was again voting in elections held on May 4, 1835, at the Tampa Precinct.

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-F3ZL-VZ5G?i=824&cat=542643

United States, Florida; Voters Registers; Florida territorial and state election records, 1826-1865; Hamilton - Jackson (June 1845); Images 824-825 of 1928

Daniel Simmons is also listed as a voter in this election, although William Sanders is not. Many of the names on this 1835 list of voters at the Tampa Precinct match the names listed on the 1833 list of voters at the Tampa Precinct (Collar, Delaney, Simmons, Conaway, Lightner, Benjamin, and Stafford). Ezekiel Stafford and LJW Roach had also appeared on previous lists of voters in Alachua and Columbia Counties (1828-1834) with Seth Howard.

All these men are certainly friends and neighbors of Seth Howard and should be researched in greater detail in hopes of learning more about Seth Howard.

So, that is conclusive evidence that Seth Howard had settled in Simmons Hammock by 1833 and was still there in 1835. He was in the right place at the right time and would have been one of the settlers who would have fled to Fort Brooke for protection once the Seminoles started burning the homesteads in Simmons Hammock and the surrounding areas.

And then I experienced a bit of genealogy kismet. I was searching for a completely different resource for a completely different project, but my search terms brought up the following item in the family search library:

There was the book Pioneer Florida, Vol II by D.B. McKay! For Free! To Download!

D.B. McKay, Pioneer Florida, Volume II, 486

Pioneer Florida, Volume II by D.B. McKay published in 1959. On page 486 it reads as follows:

This is a quote from information written by “Albert DeVane of Lake Placid” and shared with D.B. McKay.

So, who is Albert DeVane? And why is he being quoted as a source? Here is the information that I found about Mr. DeVane:

“History News.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 48, no. 3 (1970): 347–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30161520.

I have checked many places, and I have not been able to find where Mr. DeVane’s research is currently housed (There are three items housed in the “DeVane Collection” in the UF Digital Library, but none of the items pertain to the information we are presently discussing specifically). He was well-respected in the Florida Historical and Genealogical worlds. Much of his information came from interviewing pioneers and the family members of pioneers. So, now we know that this is where the information, “During the next seven years the Howard and Saunders families followed in the preacher’s footsteps, establishing farms in Simmons’s Hammock…The members of the three households in the hammock fled to the protection of Fort Brooke…Gaines reported that the three homesteads were burned to the ground,” originated. This information was originally reported by researcher Albert Devane, but we may never learn who or what were his original sources denoting that Seth Howard retreated from Simmons Hammock to Fort Brooke before the start of the Second Seminole War and that his homestead was burned along with those of the Simmons and Saunders families.

Interestingly, on page 485 of Pioneer Florida, Volume II it reads as follows:

This encouraged me to do a literature search on Mrs. Nancy Coller Jackson. It turns out that in 1900, Mrs. Jackson gave an interview to Cynthia K. Farr which resulted in a 19-page pamphlet entitled “Tampa's earliest living pioneer ... a sketch from the life of Mrs. Nancy Jackson”. Checking various places, I was unable to find a digital copy of this pamphlet. WorldCat notes that it resides in print form at two libraries.

I was, however, able to find an article on the “Digital Commons @ University of South Florida” that was written by Martha Lester Nelson in 1983 (Nelson, Martha Lester (1983) "Nancy Jackson," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 9, Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol9/iss1/8) of which the following items are sourced as having come from Mrs. Jackson’s interview with Ms. Farr:

Nancy Coller Jackson’s father, Levi Coller, was listed as a voter at the same Tampa Bay Precinct in 1833 and the Tampa Precinct in 1835 at which Seth Howard also voted. It stands to reason that even though Seth Howard is not mentioned by name in the interview given by Mrs. Jackson, he would have had a very similar experience to the one described by Mrs. Jackson at Fort Brooke in 1835.

Finally, after reading the narrative by Captain James Barr entitled, “A Correct and Authentic Narrative of the Indian War in Florida with Description of Maj. Dade’s Massacre, and an Account of the Extreme Suffering, for Want of Provisions, of the Army—Having Been Obliged to Eat Horses’ and Dogs’ Flesh, &c. &c.,” I learned that when General Gaines set out for Fort King on February 13, 1836, he did not go directly up the military road. Instead, he went East based on the word of some of the friendly Indians that there was a group of hostile Indians marauding down by the Alafia River. After finding no such band of Indians, Gaines turned north, eventually rejoining the military road to Fort King where it crosses over the Hillsborough River near Lake Thonotosassa. The men who marched with Gaines reported that the homesteads found in this area were all burned. They would have crossed directly through the area where Seth Howard’s homestead was located.

In conclusion, it is well documented that the civilians of the area surrounding Fort Brooke fled their settlements for the protection of the fort and were living there when Major Dade arrived on December 22, 1835, from Key West. Seth Howard had made his settlement in Simmons Hammock and was living there on May 4, 1835, when he voted at the Tampa Precinct along with neighbors Levi Coller and Rev. Daniel Simmons. Although no primary source documentation can be found specifically mentioning the name of Seth Howard, researching the facts noted about his various neighbors during the same period gives us a clear picture of what he endured in late 1835 at the start of the Second Seminole War.